How Do We Pronounce ん?

We have learned that the Japanese ん (n) sound, like the small っ (tsu) sound and the long vowel sound, takes up one syllable and that its length must be preserved (other articles go into detail on the issue of length).

However, what are these sounds like to begin with? Readers may find it difficult to come up with an immediate answer like “the consonant of pa/pi/pu/pe/po sounds like [p].”

ん and what it depends on

ん, small っ, and long vowel sounds are pronounced in various ways. This is because they are dependent on (assimilate to) the surrounding sounds. That is, if the sound they depend on changes, the method of dependency also changes accordingly.

With regard to ん in particular, because it has many dependencies compared to long vowels and the small っ, it is pronounced with a wider range of sounds (Table 1). As a result, learners may find it more difficult to grasp than the small っ or long vowels. However, the one common point among the sounds of ん is that it forms a nasal coda.

Table 1. Dependencies of long vowels, small っ, and ん

| Dependency | |

| Long vowel | Dependent on the previous vowel (a, i, u, e, o) |

| Small っ (tsu) | Dependent on the subsequent consonant (p, t, k, s) |

| ん (n) | (1) Dependent on all subsequent consonants (all single-character sounds and contracted sounds) |

| (2) Dependent on all subsequent vowels (a, i, u, e, o) | |

| (3) Dependent on the previous vowel (a, i, u, e, o) when there is nothing after it |

Becoming a sound like [m], [n], or [ŋ]

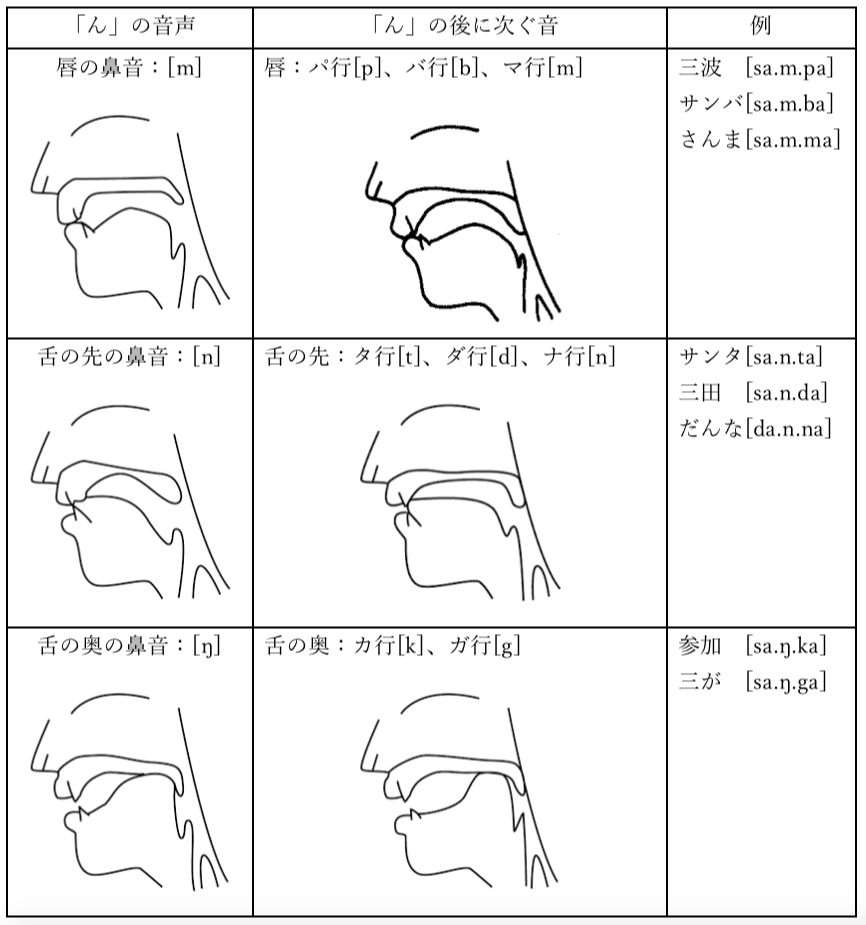

The simplest explanation of the ん sound is that it is pronounced by closing the mouth in the same way as the following consonant. We see in Table 2 that when ん is followed by a sound where the lips close (p, b, m), the ん picks this up first and is pronounced with the labial nasal sound [m] so as to close the lips in advance.

Table 2. ん becoming a sound like [m], [n], or [ŋ]

In the same way, when the subsequent sound is made with the tip of the tongue (t, d, n), ん becomes the apical nasal sound [n] made by closing off air with the tip of the tongue, and when the subsequent sound is made with the back of the tongue (k, g), ん becomes the velar nasal sound [ŋ] made with the back of the tongue.

Don’t close your mouth too tightly. Close it gently instead.

The way the mouth is closed to produce the Japanese ん sound is characterized by its gentleness (Hattori 1951, Kawakami 1977, etc.). For example, English has three types of sounds similar to ん, as in “sim,” “sin,” and “sing.” These words are distinguished by closing the mouth firmly (tightly) at the locations for [m], [n], and [ŋ].

Japanese, on the other hand, has only ん to represent the final sounds [m], [n], and [ŋ], should they exist, and does not need to distinguish the location where the mouth is closed as clearly as English does. Therefore, the auditory impression is vaguer compared to the English [m], [n], and [ŋ], and experiments have shown that it is difficult for native English speakers to perceive (Nozawa and Lee 2012).

Close your mouth more firmly for emphasis

Situations when the Japanese ん is pronounced clearly by firmly closing the mouth tend to be for purposes of emphasis or drawing attention. For example, in your Japanese language class, the teacher may have slightly exaggerated the pronunciation of ん in order to allow the students to understand their Japanese.

However, this sound bears little relation to the natural ん sound known to native Japanese speakers. In fact, pronouncing ん clearly by closing the mouth firmly tends to be negatively received by native Japanese speakers, some of whom even find that it sounds “pushy.”

Generally, the “length,” “strength,” and “pitch” of sounds are mutually interconnected. However, the Japanese ん has the unnatural characteristic of needing to be pronounced long in order to maintain the syllable length despite sounding more natural when pronounced with a gently closed mouth. This does not make for easy pronunciation, based on the general characteristics of sounds.

It is no wonder that learners struggle with it. But in order to achieve more natural Japanese, understanding where to pronounce it more gently will aid in improving your Japanese phonetics.

Becoming more like a vowel sound

Next, let’s see what happens when ん is followed by a vowel sound (a, i, u, e, o, as well as y and w sounds, which are phonetically close to vowels). Examples like “hon wo” (hon + [o]) or “hon wa” (hon + [wa]) are generally pronounced “ho’o” and “ho’wa.” This sound can be notated with a vowel lengthening sign or an added vowel; strictly speaking, it tends toward the sound called a nasal vowel.

It is well known that as a result, even native Japanese speakers can have trouble distinguishing between pairs like “gen’in/geiin (cause/hard drinking),” “ten’in/teiin (shopkeeper/quota),” and “gosen’en/goseien (5,000 yen/encouragement)” (Kurosaki 2002, Ueno 2014, Han & Namba 2020, etc.). It is, thus, not just learners who find the ん sound difficult to grasp.

Dependent on the previous vowel when there is nothing after it

So far, we have discussed what happens when ん is followed by a consonant, vowel, etc. How does the sound change in words like “arimasen” “Nihon,” “Tanaka-san,” and so on, where the word or sentence ends with ん?

In this case, ん assimilates to the preceding vowel sound, which is pronounced like a long vowel. It is different from long vowels, however, in that it is nasalized (pronounced through the nose) and more gentle (softer). This sound can be transcribed as something like “arimase’e,” “Niho’o,” and “Tanaka-sa’a,” with the last vowel softer.

Summary

As illustrated above, the ん sound is a mysterious sound which, being almost always influenced by the sounds surrounding it, can appear as both a consonant and a vowel. It is a free-ranging sound which wanders between consonant and vowel at will.

Moreover, when discovered as a vowel, it ventures into the range of long vowels, which have been reported to confuse native Japanese speakers as well. An American phonologist (Vance 2008) has described phenomena of this kind as “like a chameleon,” which I find a memorable comparison.

What is the chameleon’s real, original color? In the same way, there is no clear answer regarding the real sound of ん, and academic research on the topic continues. As someone with an interest in ん, I hope to continue observing it and clarifying it along with my readers.

Works Cited

- Uwano Zendo (2014) “Fun’iki > fuinki no henka kara on’i tenkan ni tsuite kangaeru (Considering metathesis from the ‘fun’iki > fuinki’ change),” Seikatsugo no sekai (The world of living language), pp. 8–19.

- Kawakami Shin (1977) Nihongo onsei gakusetsu (Phonetic theory of Japanese), Ohfu.

- Kurosaki Noriko (2002) “Boin ni zensetsu suru hatsuon ni tsuite: Nihongo bogo washa ni totte no chikaku no nan’i (Syllabic nasal sounds preceding vowels: Difficulty of perception in native Japanese speakers),” Kanagawa Daigaku Gengo Kenkyu (Kanagawa University Studies in Language) 25, pp. 11–22.

- Hattori Shiro (1951) Onseigaku (Phonetics) Iwanami Zensho 131.

- Han Heesun & Namba Koji (2020) “Boinkan ni okeru hatsuon no chikaku handan: Shiin no heisa no doai ni tsuite (Perception judgments of syllabic nasal sounds between vowels: Degrees of closed consonants),” Nihon Onseigakkai Dai-161-kai Zenkoku Taikai Yokoshu (Materials for the 161st Annual Conference of the Phonetic Society of Japan), 7 pages, PDF.

- Nozawa, T., and S. Cheon (2012) “The Identification of Nasals in a Coda Position by Native Speakers of American English, Korean and Japanese,” Journal of the Phonetic Society of Japan 16:2, pp.5–14.

- Vance, Timothy J. (2008) The Sounds of Japanese, New York: Cambridge University Press.